Aarhus University researchers have discovered how simvastatin, a drug typically prescribed to reduce cholesterol, also leads to significant benefits in chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, and multiple sclerosis. This discovery opens up new opportunities to treat these type of diseases.

The study “Structural basis for simvastatin competitive antagonism of complement receptor 3” was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

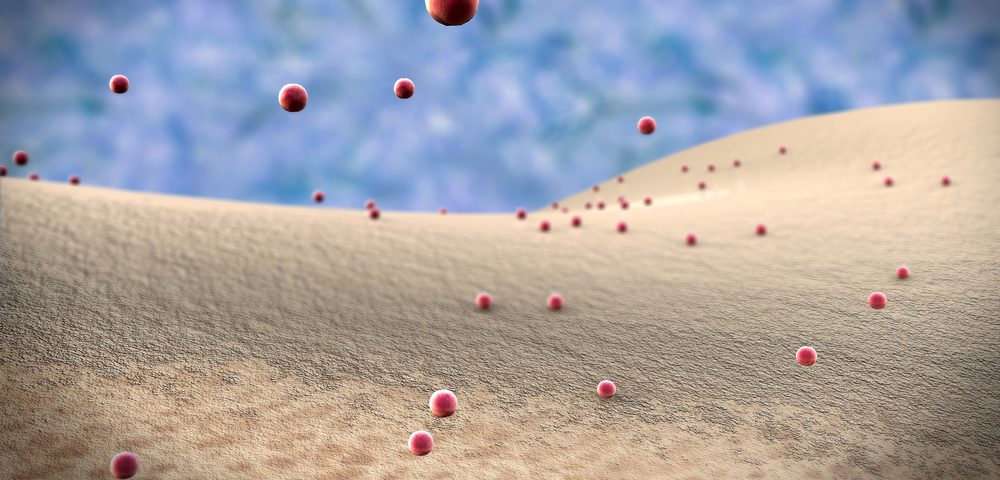

Chronic inflammatory diseases are characterized by a mistargeted attack of our immune system against our own tissues. This error, for which in most cases the causes remain unknown, leads to a chronic state of inflammation that severely damages cells and tissues.

In the case of rheumatoid arthritis the exacerbated self-directed immune system response primarily destroys the joints, while in multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes it affects the central nervous system, kidneys, and eyes, respectively.

Simvastatin has been previously shown to reduce the level of inflammation in these conditions, although the effect is often observed only when the drug is administered at high concentrations. Now, researchers have found the mechanism behind simvastatin’s reduced inflammation effect.

“Simvastatin — and statins in general — are not designed to have this effect. We have now identified a new mechanism that forms the basis for the effect, and this opens up new opportunities for developing a better substance to combat these inflammatory diseases. It’s an interesting line to pursue because a great many people can take statins without significant side effects,” Thomas Vorup-Jensen, professor at the Department of Biomedicine at Denmark’s Aarhus University and the study’s lead author, said in a press release.

Researchers discovered that simvastatin acts as a “plug” in the proteins that keep the immune cells responsible for the immune attack within the zones of inflammation. By retaining these immune cells in the inflamed areas, they are no longer allowed to travel and contribute to inflammation in other areas. This in turn decreases inflammation.

“We initially observed this mechanism in the laboratory. Of course, we now need to establish whether it works in the same way in vivo, but we think it’s likely,” Vorup-Jensen said.